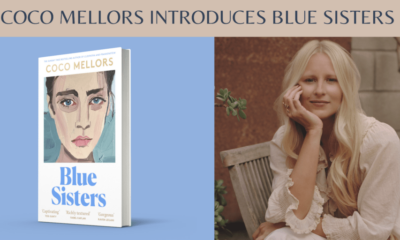

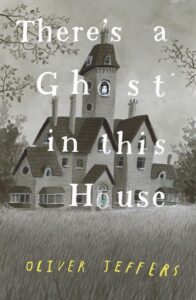

Ha ve you ever seen a ghost? The young girl in a haunting picture book hasn’t, although she suspects they might exist. As the nights draw in, young readers are invited to join her in a hunt for her elusive housemates. There’s a Ghost in this House is the latest instalment from author, artist and illustrator Oliver Jeffers, whose 2017 book, Here We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth, became a New York Times No.1 bestseller, with an Apple TV+ adaptation this year collecting an Emmy.

ve you ever seen a ghost? The young girl in a haunting picture book hasn’t, although she suspects they might exist. As the nights draw in, young readers are invited to join her in a hunt for her elusive housemates. There’s a Ghost in this House is the latest instalment from author, artist and illustrator Oliver Jeffers, whose 2017 book, Here We Are: Notes for Living on Planet Earth, became a New York Times No.1 bestseller, with an Apple TV+ adaptation this year collecting an Emmy.

In contrast to Here We Are‘s outward-looking themes, There’s a Ghost in this House reflects the lives we’ve lived indoors for over a year. This is good old-fashioned entertainment with no political agenda although that doesn’t stop Belfast and New York-based Jeffers getting passionate about politics. He chats to Antonia Charles-worth about ownership and how Neil Gaiman helped him break and enter into a creepy old house.

Tell us about There’s a Ghost in this House.

The new book is a ghostly game of hide and seek. The aesthetics of it are of an old classic ghost story with stereotypical white-sheet ghosts in various rooms created from photographs of old houses, sourced from places like architectural research books and catalogues. I’ve always worked in collage so whenever I’m at a car boot sale, a yard sale or an estate sale living in New York it’s incredible what people throw away I would collect them, thinking that will come in handy one day’. They looked like the empty scenes for something and that’s the backdrop for the tour of this house. It’s from the first person perspective of a young girl who lives in this house and has for a very long time.

Your last two books, Here We Are and What We’ll Build, addressed some big themes. Did you want to bring children some light relief this time or does There’s a Ghost in this House have some bigger concerns lurking in the shadows?

A bit of both. There’s definitely an undercurrent of this idea that you can want something so much that you can never actually get it and almost resigning yourself to the idea that you never have full control or full understanding. When I was working with organisations like the UN on climate and social responsibility following Here We Are, people would ask what I was working on next and I was like: Er, a ghost book.’ It’s a funny juxtaposition because it is just good old-fashioned entertainment in some ways.

The book is funny and sweet but also genuinely unsettling. How did you capture that balance?

There was no real checklist. I think the inherent tone of my book is charming and humorous that was coming through in spades and I was questioning whether it did enough justice to the genre of ghost books. Is it creepy and scary enough? But there is a bit of darkness and eeriness there now, with ghosts appearing in the mirror behind the girl and things like that.

What was the inspiration behind it?

There wasn’t one particular moment of Bingo! This is the story’. It was a matter of various things coming together. I love painting these old ghosts into old rooms and, when you paint that ghost onto tracing paper, you can move it around, which is always a lot of fun. Another aspect was the notion of this first-person tour through a house and not being able to find something that’s right in front of you. Slowly over time these two things began to merge. At the very start, I wasn’t sure who the ghost was, but the unlocking moment came through Neil Gaiman. I was running into this conundrum and I put it to him. He misunderstood the question and came back with something totally different. He thought that the ghosts were deliberately hiding, which is not something that I had intended but I thought actually, that will really work. That was the key to picking the lock and breaking into this old abandoned house.

Do you know who the ghost is now?

No, I don’t. In some ways the best stories that you create are ones you are only partially responsible for and they’re completed in the minds of viewers. A story doesn’t always have to be complete with a neat wrapping up of a bow. In fact, looking back through a lot of my books, it seems to very much be the case that they’re not fully resolved. They don’t just end there’s always the suggestion of more and that’s definitely the case in this one.

How do the tracing paper overlays work?

This was probably the most technically difficult book I’ve made. I thought the one that I made in Paris, The Fate of Fausto, with the classic lithography was probably going to be, but it turns out that this trumps it. The story had to be reworked and remoulded around a concrete structure of where this tracing paper could go, so the room is always on the left and the text is always on the right and in between them is the sheet. In the first few, you may not even notice it, but when you put the paper over there is a white ghost printed on it, which will then appear somewhere in the scene. It’s this idea of the power of suggestion and imagination are these ghosts really there or is this all in the imagination? It becomes more obvious as it goes on. I think we got there in the end and it works, so I’m interested to see how it goes over. I was reading it to my cousin’s kids and they started trying to predict where in the scene the ghost appeared before the tracing paper was turned over, which was something I hadn’t really thought of.

You’re planning events in New York and London around Halloween to tie in with this book. What do you think Halloween and ghost stories allow children to explore?

It’s the thing Roald Dahl touched on this ever so slight darkness that children gravitate towards because they know they’re not supposed to. It’s a chance to dress up and speak about ghosts and monsters, and kids just love that stuff. It’s all in the imagination. It’s a chance to safely play in the realm of the dark and spooky. Halloween is actually more Irish in its origins than St Patrick’s Day, which a lot of people aren’t aware of.

That raises the question of ownership of stories, which mirrors the issue of appropriation in art. Is ownership a preoccupying theme for you?

That was a big theme in This Moose Belongs to Me. The origins of that story came from reading a history of the island of Manhattan and, in particular, the purchase of that island by the Dutch settlers from the Native Americans who had always been there. The Native Americans didn’t really understand this concept of owning the land so were like we’ll take your money because who really owns anything anyway?

Look at Northern Irish politics right now and the way in which people feel so vehemently opposed to each other because of the stories that they’ve been handed down for years and years. Brexit was such a slap in the face to unionism here this idea of a Britain that that loyalist, unionist part of Northern Ireland felt very strongly a part of. It became clear that the feeling was not reciprocated. So that’s the strange shifting sea of storytelling that we’re in right now and I think watching what’s happening in Northern Ireland is going to be an interesting microcosm of what is happening in western democracy all over, particularly in the US the idea of story being more powerful than reason.

A lot of my work around space and constellations was a realisation that those lines between stars are some of the first human endeavours to make sense out of chaos and to rally our-selves around a united story. Those lines in the sky are completely made up, as are borders. People saying they have bought a plot on the moon is the same as all that colonial stuff. In Northern Ireland we still pay a tax to British landowners from hundreds of years ago. Native Americans are right to ask who really owns anything it’s just whoever has the most powerful story.

I do think that stories are probably the most powerful creation that humanity has ever come up with. It beats everything, I think, even scientific endeavour, because science ends up being the how’ based on the story or the art of the why’.

Do you believe in ghosts?

Let me put it this way: the basic principle of science is that energy cannot be destroyed, it can only be transferred, and I think that there must be some truth to the idea that people have an energy field around them good energy, bad or whatever that is. I think we’re naïve if we think that we have figured out all of the rules of energy, matter and science.

Hello, come in.

Hello, come in.

Maybe you can help me?

A young girl lives in a haunted house, but has never seen a ghost. Are they white with holes for eyes? Are they hard to see? She’d love to know! Step inside and turn the transparent pages to help her on an entertaining ghost hunt, from behind the sofa, right up to the attic. With lots of friendly ghost surprises and incredible mixed media illustrations, this unique and funny book will entertain young readers over and over again!